One vs. Two Psilocybin Doses: Unravelling the Evidence

Odyssey Take: Could Two Psilocybin Doses Be More Effective Than One?

- This suggests a second dose might reinforce and extend the therapeutic benefits. In contrast, Salvetti et al. (2024) reviewed more recent data and reached a more nuanced conclusion. They found no statistically significant difference overall between one and two doses, highlighting that factors like the therapy setting, integration practices, and patient support may be just as important as the number of doses.

- Salvetti’s findings emphasize the importance of context and preparation in determining success.For individuals who feel their first psilocybin experience was incomplete or left certain emotional material unresolved, a second dose may provide an opportunity to revisit and deepen the insights gained during the initial session. A second dose, typically spaced a few weeks apart, might also help reinforce therapeutic breakthroughs, especially for conditions like treatment-resistant depression or addiction, where longstanding patterns may require repeated intervention.

- Those seeking additional benefits from a second dose should consider whether they have fully integrated their first experience. Integration work, such as journaling, therapy, or mindfulness practices, can maximize the value of a subsequent session. Additionally, a second dose could be particularly beneficial for healthy individuals open to exploring layers of emotional material or seeking more profound psychological change.

With mental health treatment approaches expanding, psilocybin-assisted therapy has emerged as a promising option for addressing depression, anxiety, addiction, and related mental health disorders. Psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound, has gained significant attention due to its ability to induce profound psychological effects, often leading to lasting positive changes (Johnson et al., 2008). Increasing evidence also suggests that psilocybin could offer benefits for healthy individuals by enhancing overall wellbeing, fostering a deeper sense of meaning, and improving quality of life (Mans et al., 2021).

Among the pressing questions in this field is whether administering two doses of psilocybin yields better therapeutic outcomes than a single dose. This article delves into the current research, ongoing studies, and practical considerations surrounding this question, aiming to provide a comprehensive resource for mental health professionals and the general public interested in psychedelic treatments.

Psilocybin overview

Psilocybin, a serotonergic psychedelic, is metabolized into psilocin, which activates 5-HT2A receptors in brain areas involved in self-reflection and emotion regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Halberstadt, 2014). This receptor activity produces the perceptual and emotional shifts characteristic of psilocybin experiences. Psilocybin was originally studied for its therapeutic potential in the 1950s and 1960s, but clinical use ceased in the 1970s following its classification as a Schedule I drug. Renewed interest in psilocybin emerged in the 1990s, especially after safety guidelines for psychedelic administration were established in 2008 (Johnson et al., 2008).

The resurgence of psilocybin in mental health research highlights its potential as a novel approach to treatment, particularly for conditions unresponsive to traditional therapies, such as treatment-resistant depression (Carhart-Harris & Nutt, 2017). Unlike conventional psychiatric drugs, which primarily aim to manage symptoms, psilocybin has been associated with improved emotional openness, enhanced empathy, and a reduction in persistent negative thought patterns like rumination (Carhart-Harris & Nutt, 2017). These effects often endure well beyond the immediate treatment period, providing patients with a renewed capacity to approach life and relationships more adaptively.

A key focus of current psilocybin research is its influence on neuroplasticity, the brain's ability to form new neural connections and reorganize itself. This enhanced neuroplasticity supports cognitive flexibility and emotional adaptability, which may help individuals shift away from entrenched negative thought patterns (Ly et al., 2018). However, much of the research on neuroplasticity effects of psilocybin has been conducted in animal models. Although these findings suggest a mechanism that could underlie psilocybin’s therapeutic effects, further human studies are needed to confirm similar neuroplastic effects in clinical settings.

Clinical and Non-Clinical Applications of Psilocybin: One vs. Two Doses

1. Depression

Practical insights for depression: For individuals with severe or treatment-resistant depression, a second dose 3-4 weeks after the first may provide added benefits by reinforcing neuroplasticity and emotional breakthroughs. For mild to moderate depression, a single dose with comprehensive integration may suffice.

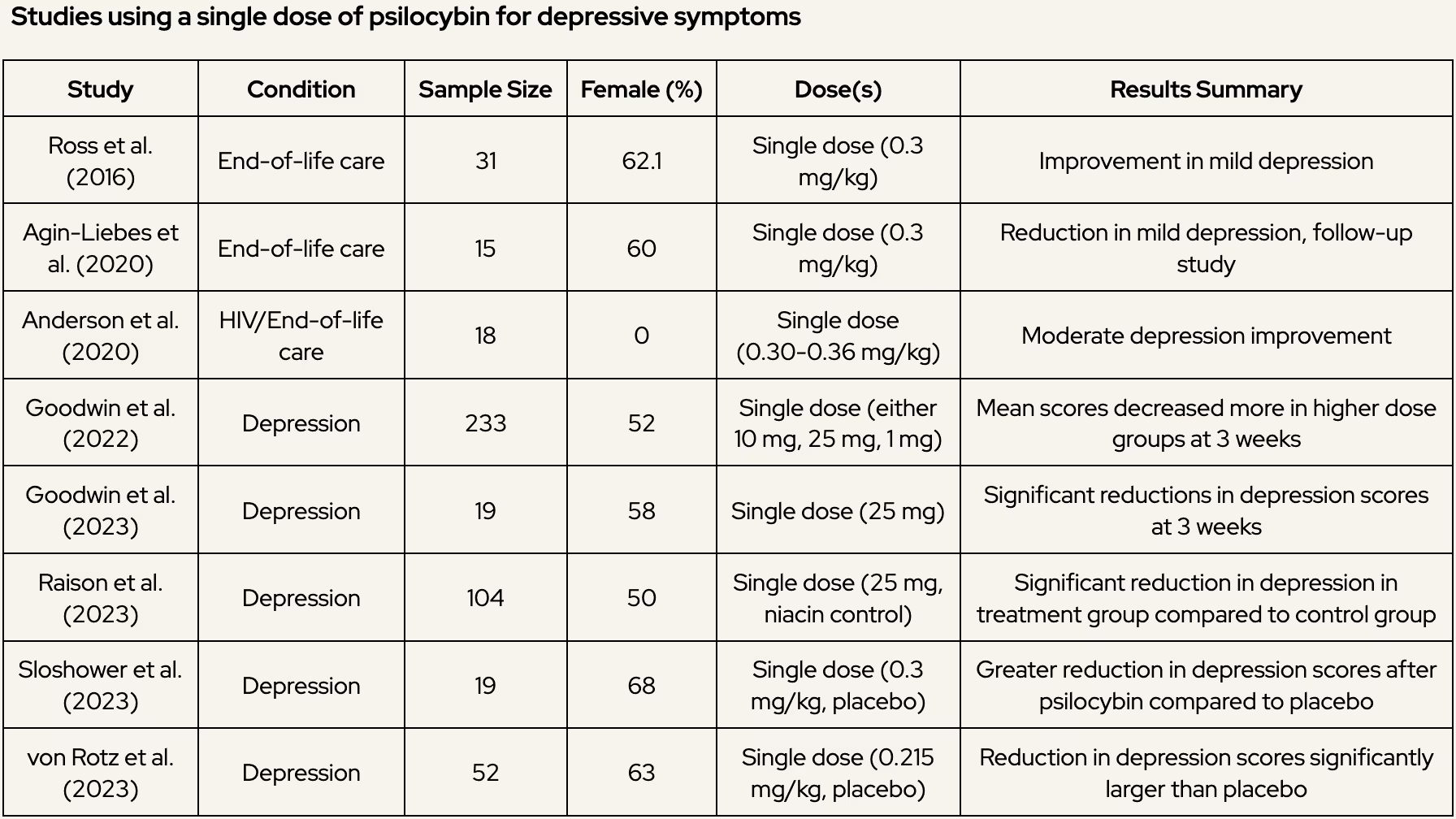

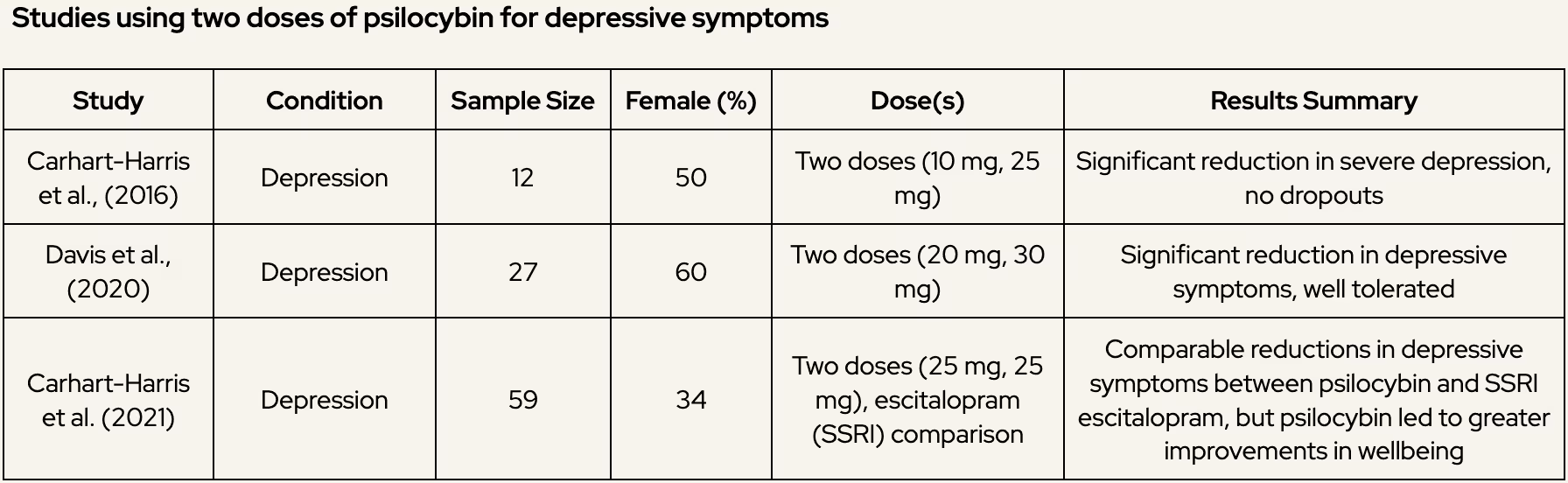

Depression has been the primary focus of psilocybin research, with numerous studies investigating its potential to provide relief for individuals with moderate to severe depression, including treatment-resistant depression. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have highlighted psilocybin’s effectiveness, whether administered as a single or double dose, in reducing depressive symptoms and sustaining these reductions over time.

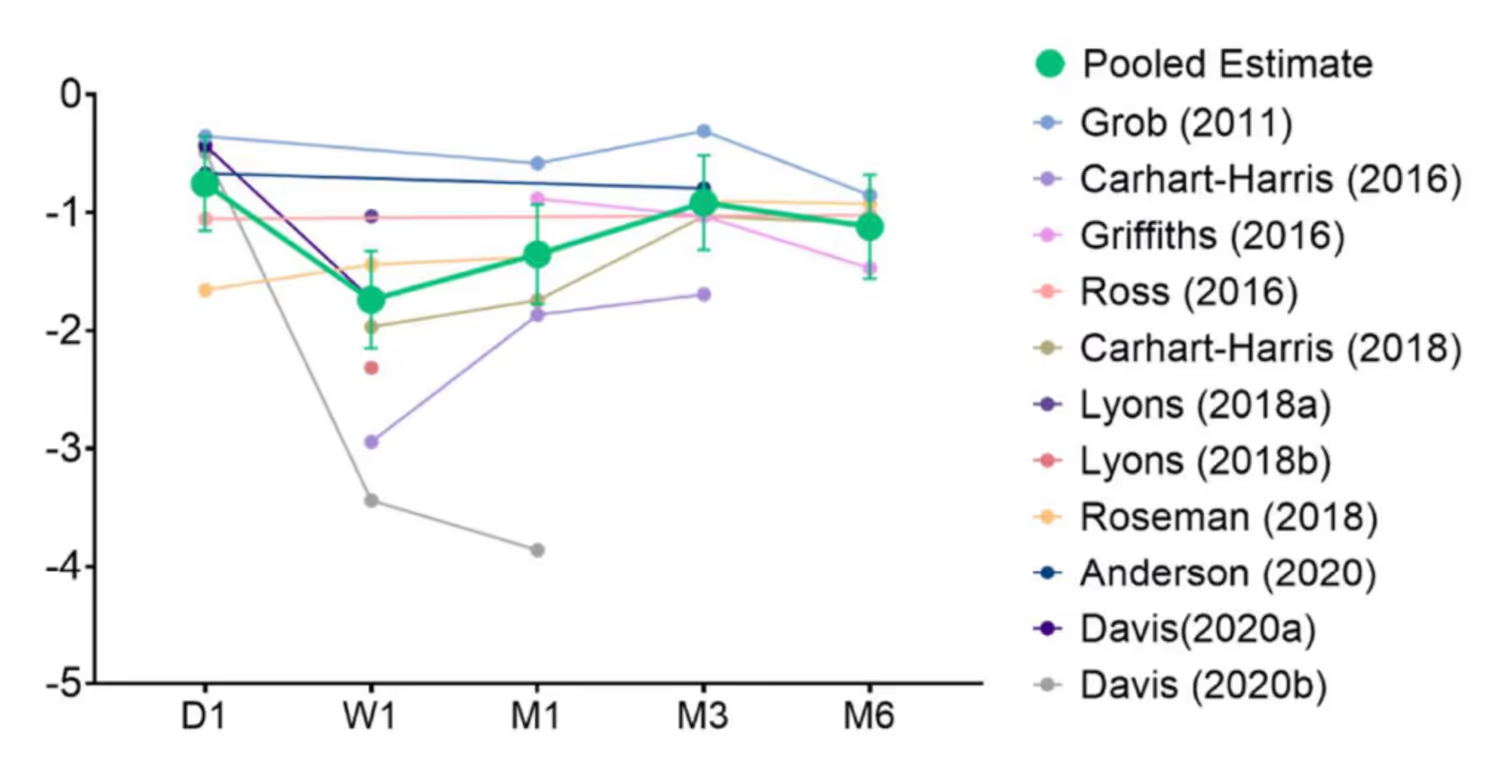

A recent meta-analysis by Yu et al. (2022) explored the trajectory of antidepressant effects following the administration of one or two doses of psilocybin. The study demonstrated that psilocybin treatment, regardless of dosing regimen, was significantly associated with reduced depressive symptoms from day 1 to 6 months post-treatment (Figure 1). Effect sizes were moderate to large, with the most significant symptom relief peaking at one week post-treatment and persisting for months. Interestingly, the analysis also found that two doses of psilocybin, normally provided between 7 days to 3 weeks, provided more pronounced and enduring reductions in depressive symptoms compared to a single dose. This suggests that the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin may be enhanced when patients receive a second dose, possibly due to mechanisms like reinforced neuroplasticity and deeper emotional breakthroughs.

However, Salvetti et al. (2024), in a more recent meta-analysis that incorporated additional studies, did not observe a statistically significant difference between single- and two-dose psilocybin protocols overall. Despite this, they noted that two doses appeared to produce more enduring effects in certain cases. The authors proposed that factors beyond dosing itself—such as therapy preparation, integrative psychological support, and dosage level per session—might play a crucial role in determining outcomes. This points to the importance of a comprehensive therapeutic framework, rather than focusing solely on the number of doses.

Psilocybin has shown promising results in reducing depressive symptoms, with effects comparable to treatments like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and ketamine, both used for treatment-resistant depression. While these therapies often require multiple sessions, psilocybin’s effects may last for months after one or two doses.

Figure 1. Trajectory of antidepressant effects of psilocybin. *** p < 0.001.

The following table provides a simplified overview of several studies exploring the effects of psilocybin on depression using either one-or-two doses regimens. This summary aims to make the clinical findings more accessible for layman readers interested in understanding the benefits of one versus two doses of psilocybin.

Learn more about psilocybin therapy for depression.

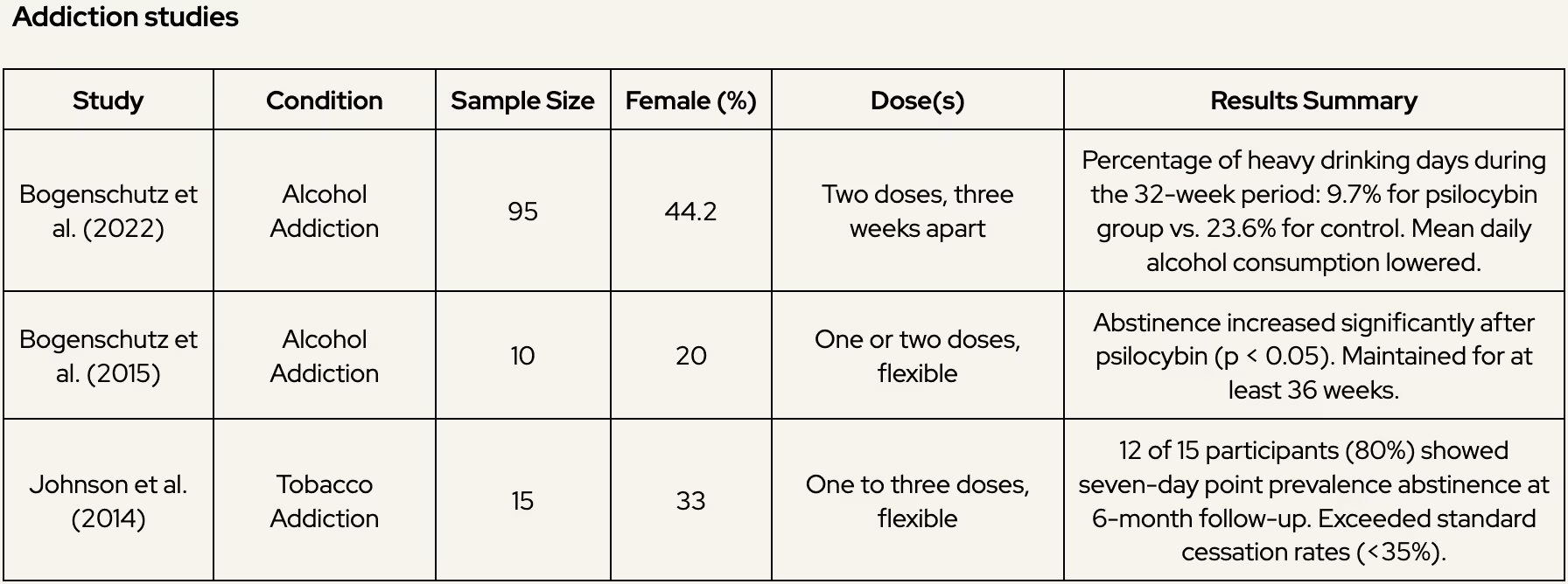

2. Addiction

Practical insights for addiction: Two doses may be more effective for individuals with entrenched patterns of addiction, as the additional session can deepen insights and motivation for behavior change.

Research on psilocybin for addiction treatment, though still emerging, shows considerable promise. Early studies suggest that psilocybin can help individuals reduce cravings, gain new perspectives on their behavior, and achieve sustained abstinence. These findings are particularly significant in alcohol and tobacco addiction, where relapse rates with conventional treatments are often high.

Alcohol Addiction

A controlled study by Bogenschutz et al. (2022) administered two doses of psilocybin three weeks apart to individuals with alcohol use disorder. Participants showed significant reductions in alcohol consumption over a 32-week follow-up period, with many reporting enhanced self-awareness and motivation to reduce drinking.

An earlier pilot study by the same group (Bogenschutz et al., 2015) also demonstrated promising results. Participants receiving one or two doses of psilocybin in conjunction with psychotherapy reported increased abstinence rates and reduced heavy drinking days at a 36-week follow-up.

Tobacco Addiction

Johnson et al. (2014) conducted a study where participants received a single dose of psilocybin combined with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for smoking cessation. At a six-month follow-up, 80% of participants remained abstinent—a rate much higher than standard smoking cessation treatments.

Other Addictions

Observational studies and anecdotal evidence suggest psilocybin’s potential for treating other substance use disorders, such as cocaine and opioid addiction. However, these areas remain largely under-researched, and further clinical trials are needed to confirm its efficacy.

3. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Practical insights for OCD: While evidence is sparse, two doses spaced weeks apart might provide added benefits for individuals with severe or long-standing symptoms.

Research on psilocybin for OCD is still in its early stages. A small-scale study by Moreno et al. (2006) demonstrated that a single dose of psilocybin could reduce OCD symptoms for several weeks. There is limited data comparing one vs. two doses, but anecdotal evidence suggests that additional sessions might help individuals confront persistent compulsions more effectively.

Learn more about psilocybin therapy for OCD.

4. Non-Clinical Intentions (Well-Being and Self-Exploration)

Practical insights for wellbeing and personal exploration: While the research is still limited, additional doses may provide additional benefits for those seeking deeper self-exploration. A second dose can help individuals revisit insights from their initial experience, process unresolved material, or explore aspects of their psyche that didn’t surface in the first session. Spacing sessions 3-4 weeks apart allows time for integration and reflection, potentially enhancing the long-term benefits.

Psilocybin is increasingly recognized for its potential to enhance personal growth, emotional well-being, and self-exploration in healthy individuals. Research indicates that psilocybin can induce profound and meaningful experiences, often described as “mystical,” which can lead to lasting psychological and emotional benefits.

Griffiths et al. (2006) conducted a foundational controlled study investigating psilocybin in healthy participants. A single moderate-to-high dose of psilocybin induced profound mystical-type experiences, characterized by unity, transcendence, and emotional connection. At a 14-month follow-up, 58% of participants rated the experience as one of the five most meaningful in their lives, reporting long-term improvements in life satisfaction, emotional well-being, and spirituality.

Nicholas et al. (2018) explored how increasing doses of psilocybin affected healthy volunteers. Participants took three doses, spaced about a month apart, in a supervised setting. The study found that higher doses enhanced certain experiences, like a sense of timelessness and connection, but having a full "mystical" experience wasn't necessary to feel long-term benefits. A month after the final dose, participants reported noticeable improvements in their overall well-being and life satisfaction.

Mans et al. (2021) extended these findings through a large-scale naturalistic observational study of 654 individuals intending to take a psychedelic substance, including psilocybin, in non-clinical settings. Using 14 measures of well-being, they found significant improvements in emotional and mental health up to two years post-experience. Participants reported changes clustering into three factors: “Being Well,” “Staying Well,” and “Spirituality.” Improvements in “Being Well” (emotional and psychological well-being) and “Staying Well” (resilience and stability) were robust and sustained, even two years later. However, this study was observational, meaning it lacked the controlled settings of clinical trials, and high attrition rates over time reduced the sample size.

These studies highlight the potential of psilocybin to foster long-term psychological growth and well-being, both in controlled clinical environments and naturalistic settings. However, findings from observational studies like Mans et al. (2021) should be interpreted cautiously, as they rely on self-reported outcomes and lack the rigorous controls of clinical trials.

Mechanisms behind the two doses approach

The therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin is rooted in its modulation of serotonergic pathways, influencing cognition, emotional regulation, and introspective thought (Halberstadt, 2014). The second dose, often administered a few weeks after the first dose, might reinforce neuroplasticity, enhancing emotional and cognitive flexibility and allowing patients to revisit and work through deep-seated emotional material (Dos Santos et al., 2021). This effect could be critical in treatment-resistant depression, where emotional breakthroughs are often important to challenge long-standing maladaptive thought patterns (Roseman et al., 2018).

In the historical context, Stanislav Grof, a key figure in psychedelic therapy, significantly influenced the understanding of multiple-session psychedelic treatment. Starting in the 1950s, Grof conducted pioneering research with LSD, eventually leading over 4,000 sessions during his career. Grof observed that a single psychedelic session often only scratched the surface of a patient’s psyche, but multiple sessions allowed patients to access and work through progressively deeper layers of unresolved trauma, unconscious material, and even transpersonal experiences (Grof, 2016).

Grof viewed LSD as a progressive “mind-manifesting” agent, enabling patients to access emotional material that might not arise in a single session. According to Grof, each subsequent session facilitated an iterative process, allowing patients to confront and integrate increasingly challenging or repressed emotions. For instance, while initial sessions might reveal conscious or near-conscious conflicts, later sessions could unearth more profound insights, such as experiences of “spiritual death and rebirth,” which Grof considered essential for emotional healing. This process often helped patients experience catharsis and a sense of resolution regarding deeply rooted psychological issues.

Grof's multi-session model introduced the concept that certain therapeutic insights, such as letting go of rigid self-identity or overcoming existential fears, might require cumulative exposure. Each session, he argued, might build on previous experiences, promoting a gradual shift in perspective that single-dose treatments may not achieve. This approach could be particularly advantageous for individuals dealing with complex psychological conditions, as it allows them to revisit challenging material with increased emotional resilience and integration capabilities after each session.

In this way, Grof’s work suggests that the advantage of multiple psychedelic sessions lies not merely in enhancing therapeutic effects but in fostering a progressive journey through psychological material. This sequential access to the unconscious is especially beneficial for individuals who require extended exploration of unresolved trauma and deeply ingrained belief systems.

Conclusions

Current evidence suggests that psilocybin offers significant benefits across a range of mental health conditions, including depression, addiction, and OCD, as well as for enhancing well-being and self-exploration in healthy individuals. Administering two doses of psilocybin may provide more robust and sustained effects for certain individuals, particularly those dealing with more severe conditions or seeking deeper self-exploration. A second dose may deepen therapeutic effects, solidify emotional insights, and enhance long-term benefits, especially for those with entrenched psychological patterns or complex personal goals. However, it also requires more preparation, integration, and financial commitment, and the added benefit may not be significant for everyone, particularly those with milder symptoms or a single-session goal. Single-dose treatments, on the other hand, have also shown substantial efficacy. For many, one dose can provide profound insights and lasting improvements, especially when combined with adequate preparation and integration.

Looking ahead, a large Phase 3 trial by Compass Pathways (COMP 006) is investigating the impact of single versus repeated doses of psilocybin across three dose levels (25mg, 10mg, and 1mg). With 568 participants, this pivotal study aims to determine whether a second dose can increase the number of responders and improve therapeutic outcomes. Results, expected in 2026, may provide critical insights into the optimal dosing strategies for psilocybin therapy.

In conclusion, psilocybin therapy, whether one or two doses, holds exciting potential as a transformative treatment. However, more large-scale clinical trials, like Compass Pathways’ study, are needed to establish definitive guidelines and fully understand the benefits of repeated doses. Until then, the choice between one and two doses should be guided by individual goals, therapeutic needs, and available resources for preparation and integration.

References

1. Halberstadt, A.L. Recent advances in the neuropsychopharmacology of serotonergic hallucinogens. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 277, 99–120

2. Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R.; Hendricks, P.S.; Henningfield, J.E. The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Neuropharmacology 2018, 142, 143–166.

3. Andersen, K.A.; Carhart-Harris, R.; Nutt, D.J.; Erritzoe, D. Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern-era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2021, 143, 101–118.

4. Johnson, M.W.; Richards, W.A.; Griffiths, R.R. Human hallucinogen research: Guidelines for safety. J. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 22, 603–620.

5. Dos Santos, R.G.; Hallak, J.E.; Baker, G.; Dursun, S. Hallucinogenic/psychedelic 5HT2A receptor agonists as rapid antidepressant therapeutics: Evidence and mechanisms of action. J. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 35, 453–458.

6. Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Erritzoe, D.; Williams, T.; Stone, J.M.; Reed, L.J.; Colasanti, A.; Tyacke, R.J.; Leech, R.; Malizia, A.L.; Murphy, K.; et al. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2138–2143.

7. Goldberg, S.B.; Pace, B.T.; Nicholas, C.R.; Raison, C.L.; Hutson, P.R. The experimental effects of psilocybin on symptoms of anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112749.

8. Davis, A.K.; Barrett, F.S.; May, D.G.; Cosimano, M.P.; Sepeda, N.D.; Johnson, M.W.; Finan, P.H.; Griffiths, R.R. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 481–489.

9. Roseman, L.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Quality of Acute Psychedelic Experience Predicts Therapeutic Efficacy of Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 8, 974.

10. Inserra, A.; De Gregorio, D.; Gobbi, G. Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanisms. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 73, 202–277.

11. Nicholas, C.R.; Henriquez, K.M.; Gassman, M.C.; Cooper, K.M.; Muller, D.; Hetzel, S.; Brown, R.T.; Cozzi, N.V.; Thomas, C.; Hutson, P.R. High dose psilocybin is associated with positive subjective effects in healthy volunteers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 770–778.

12. Dos Santos, R. G., Bouso, J. C., Rocha, J. M., Rossi, G. N., & Hallak, J. E. (2021). The Use of Classic Hallucinogens/Psychedelics in a Therapeutic Context: Healthcare Policy Opportunities and Challenges. Risk management and healthcare policy, 14, 901–910.

13. Halberstadt A. L. (2015). Recent advances in the neuropsychopharmacology of serotonergic hallucinogens. Behavioural brain research, 277, 99–120.

14. Grof, S. (2016). Realms of the human unconscious: Observations from LSD research. Souvenir Press.

15. Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187, 268-283.

16. Mans, K., Kettner, H., Erritzoe, D., Haijen, E. C., Kaelen, M., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2021). Sustained, multifaceted improvements in mental well-being following psychedelic experiences in a prospective opportunity sample. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 647909.

17. Moreno, F. A., Wiegand, C. B., Taitano, E. K., & Delgado, P. L. (2006). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of clinical Psychiatry, 67(11), 1735-1740.

18. Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., Cosimano, M. P., & Griffiths, R. R. (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Journal of psychopharmacology, 28(11), 983-992.

19. Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. Journal of psychopharmacology, 29(3), 289-299.

20. Bogenschutz, M. P., Ross, S., Bhatt, S., Baron, T., Forcehimes, A. A., Laska, E., ... & Worth, L. (2022). Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 79(10), 953-962.

21. Johnson, M. W., Richards, W. A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2008). Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. Journal of psychopharmacology, 22(6), 603-620.

22. Yu, C. L., Liang, C. S., Yang, F. C., Tu, Y. K., Hsu, C. W., Carvalho, A. F., ... & Su, K. P. (2022). Trajectory of antidepressant effects after single-or two-dose administration of psilocybin: A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(4), 938.

23. Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Nutt, D. J. (2017). Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. Journal of psychopharmacology, 31(9), 1091-1120.

24. Ly, C., Greb, A. C., Cameron, L. P., Wong, J. M., Barragan, E. V., Wilson, P. C., ... & Olson, D. E. (2018). Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell reports, 23(11), 3170-3182.

25. Salvetti, G., Saccenti, D., Moro, A. S., Lamanna, J., & Ferro, M. (2024). Comparison between Single-Dose and Two-Dose Psilocybin Administration in the Treatment of Major Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Current Clinical Trials. Brain Sciences, 14(8), 829.

26. Goodwin, G. M., Aaronson, S. T., Alvarez, O., Arden, P. C., Baker, A., Bennett, J. C., ... & Malievskaia, E. (2022). Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(18), 1637-1648.

27. Goodwin, G. M., Croal, M., Feifel, D., Kelly, J. R., Marwood, L., Mistry, S., ... & Malievskaia, E. (2023). Psilocybin for treatment resistant depression in patients taking a concomitant SSRI medication. Neuropsychopharmacology, 48(10), 1492-1499.

28. Agin-Liebes, G. I., Malone, T., Yalch, M. M., Mennenga, S. E., Ponté, K. L., Guss, J., ... & Ross, S. (2020). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. Journal of psychopharmacology, 34(2), 155-166.

29. Anderson, B. T., Danforth, A., Daroff, R., Stauffer, C., Ekman, E., Agin-Liebes, G., ... & Woolley, J. (2020). Psilocybin-assisted group therapy for demoralized older long-term AIDS survivor men: An open-label safety and feasibility pilot study. EClinicalMedicine, 27.

30. Raison, C. L., Sanacora, G., Woolley, J., Heinzerling, K., Dunlop, B. W., Brown, R. T., ... & Griffiths, R. R. (2023). Single-dose psilocybin treatment for major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 330(9), 843-853.

31. Sloshower, J., Skosnik, P. D., Safi-Aghdam, H., Pathania, S., Syed, S., Pittman, B., & D’Souza, D. C. (2023). Psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder: An exploratory placebo-controlled, fixed-order trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 37(7), 698-706.

32. von Rotz, R., Schindowski, E. M., Jungwirth, J., Schuldt, A., Rieser, N. M., Zahoranszky, K., ... & Vollenweider, F. X. (2023). Single-dose psilocybin-assisted therapy in major depressive disorder: A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine, 56.

33. Carhart-Harris, R., Giribaldi, B., Watts, R., Baker-Jones, M., Murphy-Beiner, A., Murphy, R., ... & Nutt, D. J. (2021). Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1402-1411.

34. Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., ... & Nutt, D. J. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 619-627.

.svg)

.svg)